November is National Native American Heritage Month in the United States. In observance of this celebration, the Climate Resilience Network is investigating indigenous or traditional knowledge and its use, or lack thereof, in earth and environmental sciences. Specifically, how is the scientific community using traditional knowledge to learn about and protect the Chesapeake Bay watershed?

The Chesapeake Bay watershed is home to many indigenous tribes who rely on its tributaries to sustain their daily lives. One such community is the Pamunkey Indian Reservation. This tribe is located on a peninsula in King William County, Virginia along the Pamunkey river, which flows into the York river, a tributary of the Chesapeake Bay (Hutton and Allen, 2020). Rising sea levels have caused land loss on the Reservation, encroached upon heritage sites, and limited livelihood options.

Erosion, salt water intrusion, and flooding reduce fish stocks, limit the fishing culture, reduce crop productivity, damage yards and structures, and restrict roadway access on the Reservation. The Pamunkey Indian Reservation falls within the Middle Peninsula Planning District (MPPD). Unfortunately, there are no specific guidelines to address the issues Reservation residents face in the MPPD’s All Hazards Mitigation Plan (Hutton and Allen, 2020). This disconnect could be caused by the failure to consider traditional ecological knowledge in climate knowledge and mitigation and adaptation planning.

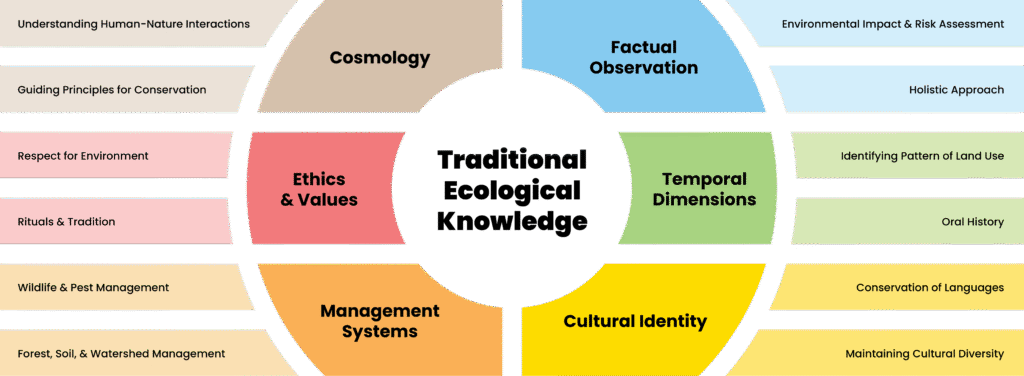

According to Gomez-Baggethun, Corbera, and Reyes-Garcia (2013), traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) consists of the body of knowledge, beliefs, traditions, practices, institutions, and worldviews developed and sustained by indigenous, peasant, and local communities in interaction with their biophysical environment. Historically, communities maintaining tight links to ecosystem dynamics have developed knowledge, practices, and institutions to accommodate recurrent disturbances to secure their livelihood. TEK can strengthen the capacity of societies to deal with disturbances and maintain ecosystem services under conditions of uncertainty and change (Gomez-Baggethun et al., 2013).

TEK can also help scientists better understand the impacts of climate change and determine best practices to mitigate those impacts that do not cause “collateral damage” to other aspects of the community. The priorities of organizations that address Chesapeake Bay conservation and other environmental issues are largely driven by ecological characteristics but neglect socio-economic and cultural priorities of community members (Hutton & Allen, 2020). In the case of the Pamunkey Indian Reservation, a fishing hut was “hastily destroyed” to install a living shoreline and bulkhead. However, if the Pamunkey community had been consulted, “the structure could have been preserved and relocated or the land beneath the shanty could have been protected with barriers” (Hutton & Allen, 2020). Climate resilience organizations and practices would be better informed by taking TEK into consideration as they plan climate mitigation strategies to avoid disruption of cultural practices and everyday life in communities.

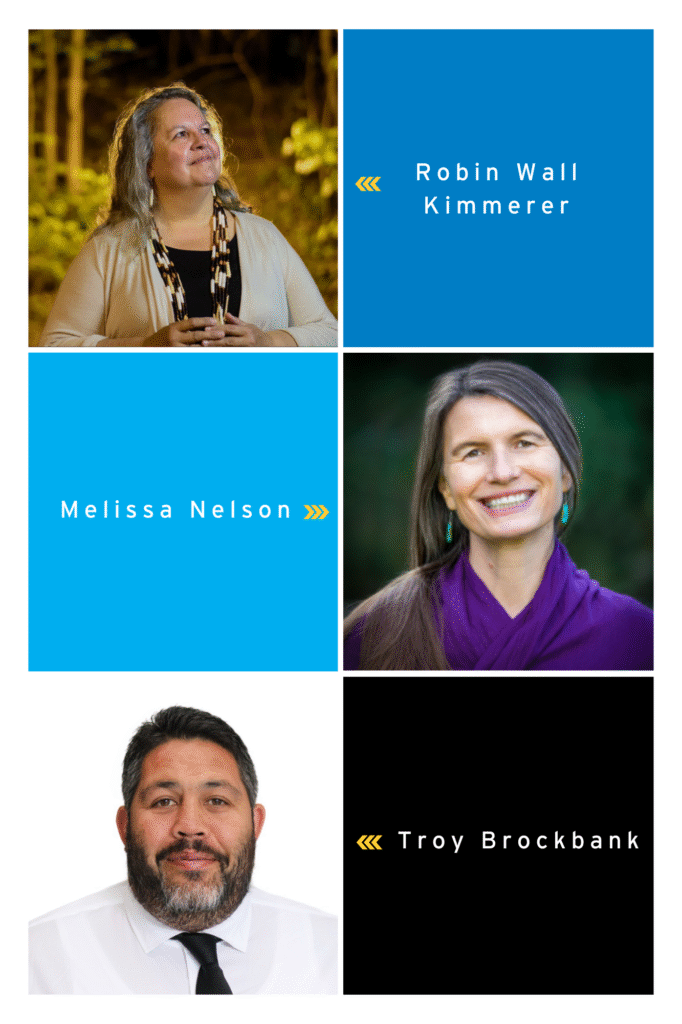

Indigenous environmental scientists working in climate resilience:

Troy Brockbank is a Maori stormwater engineer and board member of New Zealand’s new drinking water regulator, Taumata Arowai. Growing up next to a wetland, he developed a desire to protect waterways and the environment. His work involves empowering the water industry to incorporate and normalize Maori values and perspectives for the protection of water.

Melissa Nelson is a professor for the School of Sustainability at Arizona State University. She is Anishinaabe, Cree, Metis, and Norwegian. Nelson earned a PhD in ecology and Native American environmental studies from University of California Davis. Her research interests include TEK, indigenous-led conservation, and biocultural restoration.

Robin Wall Kimmerer is an enrolled member of the Citizen Potawatomi Nation. She is a writer and botanist with research interests including restoration of ecological communities and restoration of people’s relationship with nature. She earned her PhD in botany from the University of Wisconsin. Wall Kimmerer is the author of The Serviceberry: Abundance and Reciprocity in the Natural World, Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants, and other books.

These are just a few of the many indigenous scientists combining cultural knowledge with the scientific to make an impact in environmental science. But not all indigenous scientists had the opportunity or desire to pursue higher education. Anyone making observations and inferences based on those observations, are practicing science. Many communities are taking action on their own, using TEK to solve the environmental issues in their backyards. Like Robin Wall Kimmerer, mainstream science should be asking itself “How can we learn from Indigenous wisdom…to reimagine what we value most?” Do we value science for science’s sake, or science to serve communities and address global challenges for everyone?

References

About — Robin Wall Kimmerer. (n.d.). Robin Wall Kimmerer. Retrieved October 29, 2025, from https://www.robinwallkimmerer.com/about

Gomez-Baggethun, E., Corbera, E., & Reyes-Garcia, V. (2013). Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Global Environmental Change: Research findings and policy implications. Ecology and Society, 18(4). Retrieved October 22, 2025, from http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-06288-180472

Hutton, N., & Allen, T. (2020). The Role of Traditional Knowledge in Coastal Adaptation Priorities: The Pamunkey Indian Reservation. Water, 12(12). Retrieved October 22, 2025, from https://doi.org/10.3390/w12123548

Melissa Nelson. (n.d.). ASU Search. https://search.asu.edu/profile/3748589

Milligan, D. A., Hardaway, Jr., C. S., & Wilcox, C. A. (2019, September). Pamunkey Indian Reservation Shoreline Management Plan. https://doi.org/10.25773/fsaf-rz10

Palmer, J. (2021, November 21). Water Wisdom: The Indigenous Scientists Walking in Two Worlds. Eos. https://eos.org/features/water-wisdom-the-indigenous-scientists-walking-in-two-worlds