If you’ve noticed that your students are struggling to understand concepts in science, it may help to focus more on their vocabulary development. Learning science can be almost like learning a new language for our students. Understanding the language is a vital component of understanding the content. According to Davies and Gardner (2014), control of academic vocabulary directly impacts

- Academic reading ability

- Academic success

- Economic opportunity

- Societal wellbeing

Additionally, poor understanding of academic language is associated with the education gap between students of different races and socioeconomic backgrounds, as well as performance on “gatekeeping” exams like the SAT or GRE (Davies and Gardner p.1).

When you support your students’ vocabulary development, they’re overall performance in science will improve and they will gain confidence and independence. Confidence and independence are even more valuable to our students as science curricula begin or continue to emphasize student-centered and led teaching and real-world problem-solving.

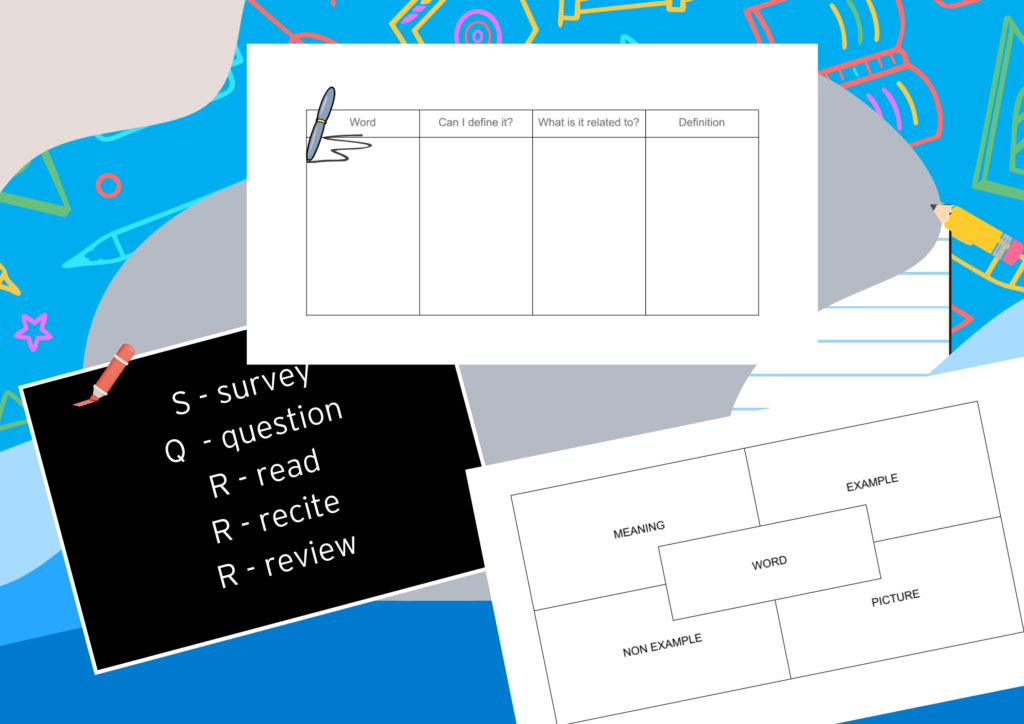

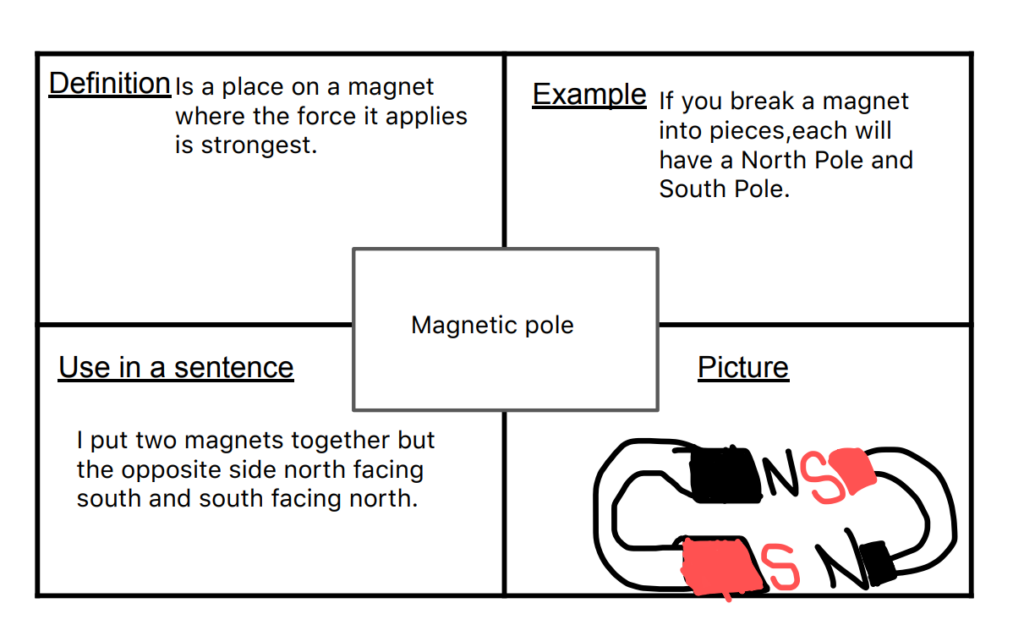

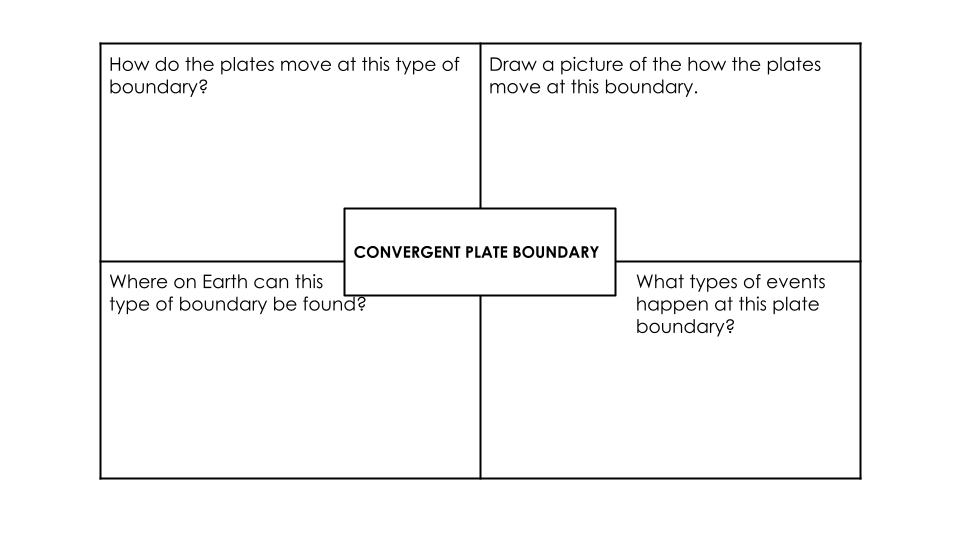

There are many ways to teach vocabulary, but whatever method or activity you choose should allow your students to organize and visualize ideas (Miller p.111). While I was in the classroom, I often opted for the Frayer model. Students can make Frayer models on worksheets, on the computer, and even on sticky notes to make meaning for vocabulary terms.

Traditionally, the Frayer model has the term in the center, with the definition, example, nonexample, and a picture in the 4 corners of the organizer. For most of my time teaching, my students, especially English learners, did not understand the “nonexample” part of the model. I did not understand the purpose of a nonexample, so I changed it to “Use in a sentence,” or “List a few related terms.” If you’re working with students who need more support, you can provide guiding questions for each section. In the example above, I graded the Frayer models for completion, accuracy, and neatness. Sometimes, I used them as a quick exit ticket or put them on the word wall at the beginning of a unit or topic.

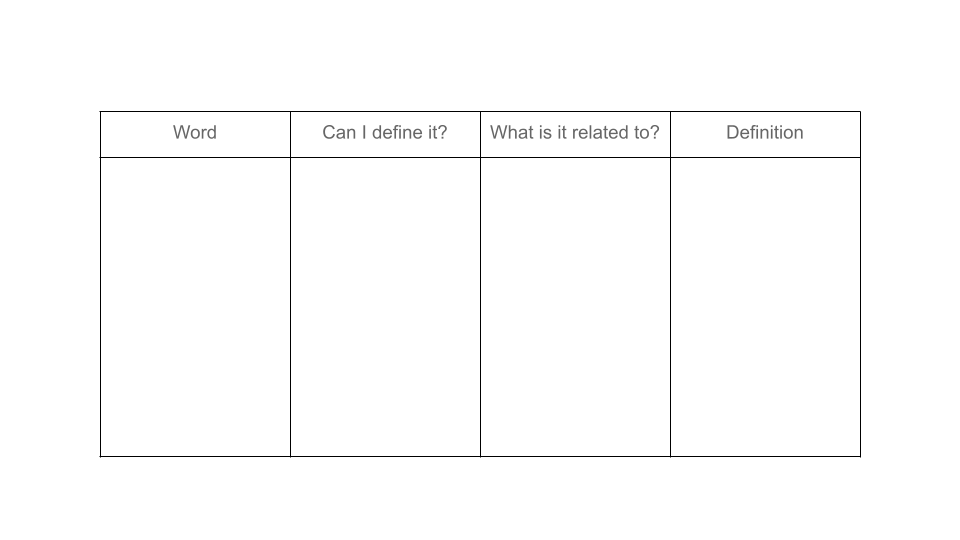

Another graphic organizer you can use to support vocabulary development is the Science Vocabulary Awareness chart. This type of organizer helps students make connections between what they are learning and what they already know (Hollabaugh p.13). The student writes the word in the first column. In the next column, they’ll answer “Can I define it” with a yes or no. Then, they’ll write what they think the word is related to or associated with. Lastly, from the text or their prior knowledge, they write the word’s definition in the last column.

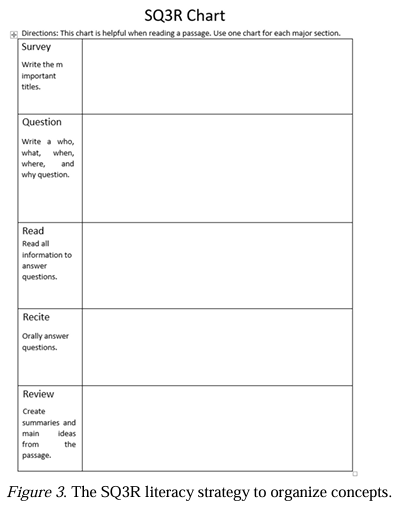

The last strategy we’ll discuss here is SQ3R. This method allows students to express cross-cutting concepts and demonstrates real-world applications of scientific vocabulary (Hollabaugh, p.15). The SQ3R method works as follows:

- Survey and Question – students skim the text, noting section headings and jotting down their questions.

- Read – students will find the answers to their questions as they read the text.

- Recite – students summarize the text verbally with a partner or independently on paper.

- Review – Students make sure they understand what they read and/or all of their questions are answered.

Facilitating the strengthening of your students’ mastery of content vocabulary could help improve their overall literacy. If you’re new to any of these or other vocabulary graphic organizers, collaborate with your school’s literacy coach or an ESL teacher colleague.

Works Cited

Davies, M., and D. Gardner. “A New Academic Vocabulary List.” Applied Linguistics, vol. 35, no. 3, 2014. Google Scholar.

Hollabaugh, Z. D. “The effect of introduced literacy strategies on the use of academic vocabulary in a high school biology classroom.“ Dissertation. 2019. Google Scholar, Montana State University.

Miller, C. “The discovery of student experiences using the Frayer model map as a Tier 2 intervention in secondary science.” Dissertation. 2015. Google Scholar, Proquest.